Different spiritual gifts

There are different kinds of spiritual gifts but the same Spirit; there are different forms of service but the same Lord; there are different workings but the same God who produces all of them in everyone. — 1 Corinthians 12:4-6

Startled by an unfamiliar sound, you awaken on a soft bed of moss in an unfamiliar forest. Your pulse quickens and your mind races. Where are you? How did you get here? Where are your loved ones? Are they safe? How can you get home? Is somebody watching you? Will the person — or people! — who brought you here return? Who dressed you? Why did they leave you alone?

After this initial burst of panic, you realize you are thirsty, and the soothing sound of water churning over rocks draws your attention to a nearby stream. The water is clear and cool, so you drink.

The sunlight sparkling in the ripples turns your eyes toward the sky. Deep blue. The air is perfectly comfortable.

The comfort of your skin reaches your ears, and you become aware of the sound of birds. Vaguely, you remember reading somewhere that chirping birds are an ancient sign of safety from predators.

Looking for the birds, you spot nearby trees and bushes bursting with fruit, including your favorite. You hadn’t realized your hunger until the moment its answer had appeared, and so you eat. The pleasure of the taste fulfills more than your belly.

As you reach for more, you feel a soft pressure on your leg. A friendly representative of your favorite kind of animal has appeared to investigate and befriend you.

Now you spot an inviting path into the trees, and you are about to explore when you hear what sounds like gunshots. They are in the distance but unmistakable. Hunters? An explosion insists on something worse, and then the sounds of screams and shouts. The forest darkens as a cloud covers the sun.

Before you have answered what next, a persistent buzz assaults your ears. Turning slowly, you find a horror hovering before your face. A thing, a mechanical bug thing glares at you through a single camera lens, and as your eyes focus, you see a menacing needle jutting out from below the glass. It drips a sickly green fluid, and though you do not look, you imagine the drop steams when it hits the ground.

A harsh voice barks from the bug thing: “Follow the drone.” You cannot do otherwise than obey.

The country that you gradually discover is full of despair and suffering, its people oppressed. Although the sun still shines, the haze of living strain saps it of its enlivening power. A sense of dread overruns every scene, robbing water of its ability to refresh, food of its flavor, and companionship of its comfort. But a hint of hope persists in a mystery.

Gradually, you discover that you are the child of an absent king, and although he’s let this country go wild, he has promised to reclaim it. Responding to the call of this adventure, you resolve to kindle and enflame the hope so that others do not let their temporary despair lead them to irredeemable ways of looking at life.

The world is not a paradise, even though — at times — the possibility seems tantalizingly close, but neither is it a dystopia, even though the hope of a better life can flicker as if it might be extinguished. You tell them that the light can never fail; it is always there if only you remember what world you live in.

Featured image by Justin Katz using Dall-E 3.

Sometimes we just can’t understand why God doesn’t answer our prayers.

Certainly, the collection of promises and reasoning in Judeo-Christian scripture and tradition may create the feeling that, when we ask for things, God should give them to us. Our modern sense of ourselves as choice-driven consumers who rightfully select the best option on offer amplifies the sense. A God who wants us to worship him should make it worth our while, so to speak. Yet, the transactional view of prayer is among the first misimpressions that one must overcome to grow in faith.

Corrective homilies will periodically clarify that God gives us what He knows we need, not what we presume to request, and that may be a suitable bandage for slight spiritual wounds. When our faith will largely heal itself from a mild cut, the priest or spiritual advisor need only offer some comfort and aid against infection. But for deeper gouges — when the weight of life seems unreasonable, while the requests we make of God in response seem modest — something more profound is needed.

Unfortunately, such somethings fall very steeply into deep theology, which a person under duress may find impenetrable. In a contemplative state of mind, we might agree that free will and Original Sin explain why suffering is necessary, and surely, we can recognize that the promise of eternal life with God is magnificent. But when we feel most in need of comfort, we long for a taste of the magnificence now, as a mild bit of material mercy in this life, and if God withholds even that, what are we supposed to do?

A good starting point might be to put aside the deep philosophy and the cosmic focus. Simply put, life is a relationship with God, and in any relationship, you speak or act, and the other person responds. That’s what a relationship is. The crisis of unanswered prayers, then, comes when your incredibly powerful Friend not only doesn’t appear to help, but seems not to respond at all.

No general advice will help, here. Your relationship with God is your existence, and your particular trials are unique to you. To know what formula to recommend, a human advisor would either have to be very lucky or know you as intimately as you know yourself. Meanwhile, the problem with asking the Person who knows you most intimately, God, is that He cannot take you aside and explain what He’s doing without changing your very experience of existing. Unambiguously articulating His advice would change the very world in which you perceive yourself to live, which may or may not be what you need.

“Have you come to believe because you have seen me?” Jesus asks Thomas, who doubts the Resurrection (John 20:29). Well, “Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed.” Without having seen God explicitly, such people maintain the intimacy of seeing Him implicitly. That’s a different relationship, and it’s arguably preferable.

So, while in the shadows of doubt, think, first, in terms of how you communicate with God and, second, how you’d expect somebody who knows you as well as He does to communicate with you. On the first count, because the relationship is your existence, your communication takes the form of your attention, which you direct in four ways:

- In the choice of where you turn your senses — what object and at what level of detail you choose to observe the world around you

- In the perspective with which you process what you observe — whether positive or negative, hopeful or despairing, in search of evidence of God’s hand or its absence

- In the place to which you go in order to observe — inasmuch as you are thereby choosing what will be present to you

- And by means of acting in the world — whereby you determine what actions on your part Creation is responding to

The joy of a genuine relationship is in getting to know the other person, and to do that, one must account for one’s self. What aspect of my friend did I turn my attention toward? What was I looking for when I turned my attention there? What would I expect to find when I go to this or that room of his or her house? And to what action of mine is he or she responding?

A recent experience brought these ideas together for me. The pressures of life have been growing, especially in financial terms, so one morning this week, I woke up asking for support. Generally, I was praying for a signal from my Lord that He has me in view — that things are fine. Truth be told, though, I had in mind something like an anecdote from Jonathan Roumie, who plays the role of Jesus in The Chosen.

He’d been trying to make ends meet with multiple jobs while working as an actor and had reached the point of little to show and unpayable bills looming. So, he handed the problems over to God and simply asked to be shown what path he ought to follow. That day, several unexpected residual checks arrived in his mailbox, sufficient to cover his short-term expenses, and soon thereafter, The Chosen opportunity arrived.

The circumstances of a single actor are quite different from those of a father of four, but that’s the sort of thing I was hoping I’d receive through my prayer: a big “yes” to stay on my path or a big invitation to take another. Working from home, I watched the mailman come and go, and I walked out to the mailbox, not really expecting anything. Among the usual bills and junk mail, I found an envelope with the phrase, “class settlement,” in the return address. Standing in the street, I opened the envelope. I could see the border pattern of a machine-printed check inside; the top fold of the paper quickly explained it was my share of a class-action lawsuit I didn’t realize (or had forgotten) existed.

I looked at the check and laughed! $5.53. “Point taken, God.”

A little while later, I doubled down on my folly. Although even saints and religious, such as Thomas Merton in Seven Story Mountain, admit to having done it, Christians are generally discouraged from testing God with such trifles as opening the Bible and pointing to a line on the page. Nonetheless, a little while after discovering my underwhelming financial windfall, it occurred to me to see what I might find on the corresponding page, 553, of my desk copy of The New American Bible:

Psalm 11

Confidence in the Presence of GodIn the Lord I take refuge;

how can you say to me,

“Flee like a bird to the mountains!

See how the wicked string their bows,

fit their arrows to the string

When foundations are being destroyed,

what can the upright do?”The Lord is in his holy temple;

the Lord’s throne is in heaven.

God’s eyes keep careful watch;

they test all peoples.

The Lord tests the good and the bad,

hates those who love violence,

And rains upon the wicked

fiery coals and brimstone,

a scorching wind their allotted cup.

The Lord is just and loves just deeds;

the upright shall see his face.

Point taken, indeed! When the foundations of our material lives are threatened, what can we do? Only look to God — look for God in everything. A laughably inadequate bank check bringing humor and a comforting hidden message to put my problems in perspective is exactly the sort of message I’ve grown to recognize as friendship from other people. It’s not an offer to save the day or solve the problem. It’s not even so striking that one couldn’t dismiss it as coincidence. It was only precisely what I needed: a smile with permission to continue finding my own way forward. And the next step in this relationship is to decide how to respond.

Featured image by Justin Katz using Dall-E 3.

As an appropriate vignette of the near future of modern life, somebody recently directed my attention to this short movie from The New Yorker:

The title and plot description of the video cued my internal consideration of the topic of AI and relationships. Is computers’ ability to fabricate communication in ways that are increasingly difficult to differentiate from human interactions a positive development?

I can remember when the Internet was new, and on lonely nights, I’d find myself — rather than clicking through the television channels — searching for something online that felt like a human interaction. Blog comment boxes and chat rooms worked, to some degree, and social media has become nearly an addictive digital pathogen to satisfy the impulse. Turn that technological dial one click, and a person who is largely disconnected from others by the distance of screens can lose his or her sense of the importance of real people.

The distinction, here, relates to the Catholic view on end-of-life decisions. A feeding tube can be understood as akin to a long spoon, and so withholding that assistance would be immoral. A device that forcibly operates failed organs is on the other side of the line, as an “extraordinary measure,” so while we shouldn’t arbitrarily deprive people of them, ceasing their operation involves a different moral calculus than mere assistance. Such distinctions require deeper thought than many people may find natural, but it does matter whether the “person” with whom (or “which”) one communicates is a living, breathing human being.

In a dark, inverted way, “Rachels Don’t Run” points to two related reasons why. The surface reason is the unpredictability. Sure, AI could add a randomness variable, or the algorithms could become better at tricking people into sensing unpredictability, carefully crafted to evoke the response that the AI or (at first) its designers want. Nonetheless, the viewer (probably) expects an enriching outcome when Leah, the main character, breaks into the inhuman conversation and surprises Isaac.

When that outcome doesn’t materialize, the deeper reason a real human matters becomes apparent: a genuine relationship imposes responsibility. Isaac responds as he does because Leah claimed the connection without his consent. He didn’t want a genuine relationship. He wanted cooing affirmation.

Ultimately, mutual responsibility defines “relationship,” and in a world of autonomous choice, people may interpret as presumption others’ attempts to connect with them. The danger arises because this definition of “relationship” extends to God (or “life,” for those who prefer to characterize it as such). An Isaac who prefers to cultivate interactions with a digital slave lives in a solipsistic world wherein the “other” does not really exist and is there to serve him.

The viewer shouldn’t overlook the fact that Leah and Isaac both miss their mothers — representing the quintessence of responsibility — and the moment of crisis comes when Leah implies she is beginning to feel her responsibility to her mother might not mean eternal sadness about her passing. Notably, the character who reached out for a genuine human conversation was further along, in this respect, whereas the other wanted to wallow in “going through a lot, right now” — which desire seems apt to lead to long-term depression when enabled by AI.

My prayer practices have varied over the years, as I’ve come across new materials and new ideas and as my schedule has changed, but with a general increase in time and discipline.

For a while, I kept up a somewhat irregular devotion to the canonical hours, using a daily psalm book I received as a gift when I converted. I loved the feeling of connection to texts dating back to the Old Testament and the sense of a monastic ritual. As a complete prayer routine, however, the Old Testament feel can use some Anno Domini leaven.

At periods, I’ve maintained a daily Rosary on my schedule, and it is a practice I recommend whole heartedly. On my desk sits a handmade leather notebook with pages that may very well have been fashioned by hand, as well. Its pages contain an as-yet incomplete penciled series of prayers built around the Rosary, with readings I selected to correspond with the Mysteries. For my own daily life and spiritual condition, however, the time and repetitive nature of this prayer led me to substitute more variety.

These days, I’ve settled into a routine that seeks to balance different forms of prayer, from Bible reading to credal recitation to requests for intercession to something more like meditation. In what follows, I describe the set of prayers with which I begin my day.

Upon waking, I thank God for allowing me another day to spend with Him in His creation. After taking care of some early necessities and stretching, I light a candle and kneel using a wooden library stepladder with a pillow on the lowest step. With a dash of holy water, I prepare myself, as I do for each of my daily prayer sessions, as follows:

I choose to be fully present in this moment, to observe it with all my senses, and to feel Your presence in it, oh sustaining God. I put myself fully in your embrace, to feel you support me, engulf me, enter me, as me. And moving forward from this moment, I choose to grow in my relationship with and understanding of You and to fulfill my role in your plan.

Depending on my mood or needs of the moment, I’ll exchange the adjective, “sustaining,” for something more relevant, such as “magnificent,” “comforting,” or “forgiving.” I inhale while whispering the phrase, “enter me,” for the sensation of air across my tongue, as that which God created communicating with me physically as a means of maintaining my existence.

I considered the phrase, “as me,” carefully, and recognize it as a point of risk if it takes too much of a New Agey tilt, and certainly, my full theological framework might strike some traditionalists as too far in that direction. However, today’s second reading at Mass offers the appropriate ballast: “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ? But whoever is joined to the Lord becomes one Spirit with him.” (1 Corinthians 6:15,17)

In the morning, my purpose is to prepare myself for the day, and I find it appropriate to frame that activity in terms of spiritual warfare. Over time, I cycled through the prayers published in a small booklet I picked up long ago in the shop at the National Shrine of Our Lady of La Salette, titled “Spiritual Warfare Prayers.” At some point, I simply memorized this one, which I found particularly powerful:

I armor myself today with the power of the Most Holy Trinity, in the oneness of God, Creator of the universe. I armor myself today with the baptism of Christ, his crucifixion and resurrection, his ascension and glorious second coming.

I armor myself today with God’s guidance to direct me, God’s might to sustain me, God’s wisdom to instruct me; God’s word to give me speech, Gods shield to protect me; Gods army to defend me against the snares of the demons, against the lure of vices, against all who plot me harm.

I invoke all these virtues today against every hostile and merciless power that may assail me, against the incantations of false prophets, against the black laws of heathenism, against the false laws of heresy, against the deceits of idolatry, against every art and spell that binds the soul to evil.

Christ guard me today against every poison, burning, drowning, and fatal wounding. Christ be with me, Christ be behind me, Christ be within me, Christ be beside me, Christ to win me. Christ to comfort and restore me, Christ to be where danger threatens, Christ be in the hearts of those around me forevermore.

Next, I turn my thoughts to daily reminders, blending together those of a spiritual nature with others that are more practical or targeted toward self-improvement. These change over time, and I’d encourage anybody who likes the idea of the list to make it his or her own. At the moment, I have 29:

- Find something to appreciate in every moment.

- Set aside dedicated time for God.

- Everybody deserves attention and patience.

- Break a sweat.

- Play an instrument.

- Never more than two alcoholic drinks.

- Keep kids on schedule.

- Spend special time with your children.

- Challenge the status quo firmly and confidently; people are suffering out there.

- Be moderate in your appetite.

- Please your wife.

- Charisma equals presence, warmth, and power.

- Look for opportunity to get where you want to go no matter where it is you have to be.

- Make menial tasks not menial.

- Cultivate a desire to help in your children.

- Continue with the self-analysis.

- Ensure that every task is the highest and best use of your time, given circumstances.

- When distracted with the need for engagement from others, don’t forget to consider those closest to you — God first among them.

- Approach each day as an opportunity to spend time with the most important Person in your life.

- Stay present in the moment, even as you think forward to the message you wish to send to God with your life.

- Find the framing that makes the obscure or complicated obvious and simple.

- Healing embraces reach out to God in others with your arms as His.

- You matter so much that what happens to you matters very little.

- In your community and in your work, you are here to learn; you do not need to win.

- In the light of eternity, fidelity to God, not material achievement will shine.

- The serenity of your heart cannot be disturbed if you live in God.

- The path does not matter as much as the way in which you travel it.

- Remember what world you live in.

- Lord, Jesus, look at me through their eyes, and I will respond.

Having drawn myself into God’s presence in the moment, prepared myself as if for spiritual battle, and reminded myself of collected advice and wisdom, I call on Saint Michael:

Saint Michael, please pray for me that I will have the strength to resist the Devil’s temptation toward doubt, despair, anger, anxiety, indifference, lethargy, pride, and decadence and send an angel to guide and guard me throughout the day as I seek to do God’s will. Pray that Our Lord, Jesus Christ, will send His Spirit upon me so I may better understand my role in the Father’s plan. And please, Saint Michael, with my guardian angel, give me a sense of your presence so that I may feel myself a member of the community of souls and not be vulnerable to the isolation of the modern material world.

I tack on to this any specific needs I feel at that moment, whether for health or other aspect of life and then ask Saint Michael to “pray for my loved ones and send angels to guide and guard them all.” I name each of them, more or less from youngest to oldest, specifically naming any specific intentions for each, with strong emphasis on their health and growth in faith. For those who are deceased, I ask Saint Michael to “have your angels find her wherever she may be and draw her toward our Lord” (changing the pronouns as relevant). Having named my family members, I ask, “Saint Michael pray for my household.”

Next, I move outward, breathing in deeply as I zoom out from the globe in my mind and asking for prayers for escalating geographic units and the corresponding divisions of the Catholic Church. First is Tiverton, and I name the parishes in the town, followed by the State of Rhode Island and the Diocese of Providence, the United States of America and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and “all of us on the planet Earth and in the Roman Catholic Church.” At each level, I bring to mind any specific people who have acute needs at that time.

How long, O Lord? I cry for help

but you do not listen!

I cry out to you, “Violence!”

but you do not intervene.

Why do you let me see ruin

why must I look at misery?

Destruction and violence are before me;

there is strife, and clamorous discord.

This is why the law is benumbed

and judgment is never rendered:

Because the wicked circumvent the just;

this is why judgment comes forth perverted. (Habukkuk 1:2-4)

Times are dark, indeed, when one looks to the prophetic books not for warnings about what could be but comfort in what has been before. But here we are.

Last week, I wrote in despair for the Roman Catholic Church. Peculiar as it may be, doctrinal documents from the Holy See have been crucial to my faith. Two circumstances apply. The first (and most straightforward) is their articulation of ideas that ring true and, moreover, that arrive theologically where the scientific and philosophical disciplines will only later tread. Understanding of the Trinity and the Logos, the balance of solidary and subsidiarity, and the distinction between substance and accident in the Eucharist are examples of concepts that ring true and that, when applied to, say, science, move one further faster than a materialist approach allows.

The second circumstance in which doctrinal documents have confirmed my faith in the Church is less intuitive: when the reader can tell that the writer really wants to accommodate something that precedent will not allow… but cannot.

In academic, legal, or popular texts, attempts to wish away obstacles of logic and reality are visible to those who wish not to be taken in. The writer brings an idea to a point of crisis and then through some sort of pivot, ambiguity, or rhetorical gimmick leaps across the intellectual chasm. A recent and profound example comes from Andrew Sullivan, from his book, Virtually Normal, a polemic on behalf of same-sex marriage before it had been imposed:

Some might argue that marriage is by definition between a man and a woman; and it is difficult to argue with a definition. But if marriage is articulated beyond this circular fiat, then the argument for its exclusivity to one man and one woman disappears.

The fact of the definition held within it the core of the point. “Articulating” marriage “beyond” it neatly discards both the etymological reason and the effect of every instance of the word’s current usage. One puts aside all traditional explanations and changes the law by changing the meaning of the text.

Unsurprisingly, a classic example comes from Karl Marx, one of history’s most prolific practitioners of such tricks. In his Economic-Philosophic Manuscripts, he must inevitably face the problem that his philosophy hits a wall with the origin of man, and his response is to mumble around on the word “existent,” concluding with this diabolical punchline:

I say to you: Give up your abstraction and you will also give up your question. … Do not think, do not question me, for as soon as you think and question, your abstraction from the existence of nature and man makes no sense.

Your argument cannot disprove his thesis because he has declared impermissible any ideas outside his careful boundaries. True to Marxist form, however, his proscriptions do not apply to himself. His writing proceeds through a tangle of abstractions asserted to be concrete observations and words that don’t quite mean what he uses them to mean. From these fibers of inconsequential ideas with no consistent, coherent thread of truth he spins a noose with the strength to strangle nations. Accept the premise that he might not be a rambling lunatic, and you are already dangling above any firm foundation from which to disagree with him.

In contrast, Church doctrine maintains that thread of Truth — a consistent end-to-end line that prevents the surrounding tangle from bending in whichever direction or blending with whatever material the rhetorical weaver might wish. The Faith is affirmed in the tacit admission that they can only go so far and no farther.

Tragically, “Fiducia Supplicans” bears the tell-tale marks of the trick. The declaration pretends to say what it does not say so it can be understood to mean what it cannot actually mean and still be Catholic. Like so:

Within the horizon outlined here appears the possibility of blessings for couples in irregular situations and for couples of the same sex, the form of which should not be fixed ritually by ecclesial authorities to avoid producing confusion with the blessing proper to the Sacrament of Marriage.

One brazen lie on which its advocates have relied to fend of objections is that “couples of the same sex” can be translated as “two individuals who happen to approach the priest at the same time,” which is not what anybody reading the document will understand it to mean. The tell-tale mark, however, is the phrase, “within the horizon outlined here.”

In writing that styles itself as intellectual, reference to “the horizon” is often a lazy linguistic tic, like “moreover” or “furthermore,” allowing the author to avoid the work of drawing genuine connections between ideas. It means that, although we cannot see the thing clearly enough to explain it, we can pretend we don’t see a contradiction within our range of sight. The writer fancies he or she has sketched a circle so wide that two contradictory things can both fall within it. Somewhere between where we stand and our conceptual horizon, a justification might exist, even if we haven’t found it, yet, so we can behave as if it does exist, despite millennia of precedent to the contrary.

Victor Manuel Fernandez cannot succinctly articulate how his “innovative contribution to the pastoral meaning of blessings” is consistent with the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church because the thread of Truth will not permit him to. So, instead, he has handed us a mess of thoughts so jumbled that anybody who does not reject it outright must admit his or her own inability to see a problem.

So familiar is this evil gimmick that my very being cries out that this document belongs nowhere near the legitimate doctrine of the Catholic Church, and anybody who does not actively reject it is out of conformance with the Truth. Hence my lamentation that its acceptance by Pope Francis and the Holy See effectively excommunicated the entire Church and all its members, including me.

Conversations and consultations, along with much reading and prayer, have pulled me back from this ledge. Whatever the condition of Pope Francis’s intellect and soul may be, that the Holy Spirit has not permitted falsehood to be declared as an infallible teaching means the Church, herself, continues to hold that thin, strong thread. By this thread, we are still connected to the Lord, as we are connected with each other, even those who are in error, as (I believe) Pope Francis and Cardinal Fernandez are.

Indeed, the thread — what it means to be “in communion” — is strengthened to the extent we seek never to lose these connections. I must hope, through my prayer, to draw these men away from error, and I must understand that, in some instances, they may do the same for me.

The ancient prophets’ warnings present terrifyingly familiar images:

After their reign,

when sinners have reached their measure,

There shall arise a king, impudent

and skilled in intrigue.

He shall be strong and powerful,

bring about fearful ruin and succeed in his undertaking.

He shall destroy powerful peoples;

his cunning shall be against the holy ones, his treacherous conduct shall succeed.

He shall be proud of heart

and destroy many by stealth.

But when he rises against the prince of princes,

he shall be broken without a hand being raised.” (Daniel 8:23-25)

As we find comfort in the familiarity of times when darkness loomed but the promise of redemption was not dimmed, we must take the draught in its fullest measure. Through Ezekiel God proclaimed: “The end has come upon the four corners of the land! Now the end is upon you; I will unleash my anger against you and judge you according to your conduct and lay upon you the consequences of all your abominations” (Ezekiel 7:2-3). And even in His wrath, He “called to the man dressed in linen with the writer’s case at his waist, saying to him: Pass through the city and mark an X on the foreheads of those who moan and groan over all the abominations that are practiced within it,” and He instructed His destroyers, “do not touch any marked with the X” (Ezekiel 9:3-6).

Yet, that is not the end of it. In our connection to others we have the responsibility to warn them, and not only the wicked:

If a virtuous man turns away from virtue and does wrong when I place a stumbling block before him, he shall die. He shall die for his sin, and his virtuous deeds shall not be remembered; but I will hold you responsible for his death if you did not warn him. When, on the other hand, you have warned a virtuous man not to sin, and he has in fact not sinned, he shall surely live because of the warning, and you shall save your own life. (Ezekiel 3:20-21)

To avoid culpability, we must alert others to their errors, while remembering that we are not marking them for special condemnation, as was a common temptation in eras past. The chief temptation of our era, by contrast, is to imagine we have come into possession of the angelic writer’s case and can mark others as virtuous, whether or not they moan and groan over abominations.

In these times, when it seems our souls stand on a thread too thin to see, and the weight of our comfort and ease feels as if it must cost us our balance, we cannot spend our time scanning the horizon for innovative spiritual destinations. But neither can we push off those with whom we disagree while clinging to those we find easy to embrace. In either of those ways we lose our grip on the crucial fact: The thread of Truth is not a tightrope providing a rare protection against the more-real gravity of the abyss. It is, itself, the center of gravity for all who do not will themselves to plummet, and the more we reach out to save others, without letting go of the Truth, the more it will hold on to us.

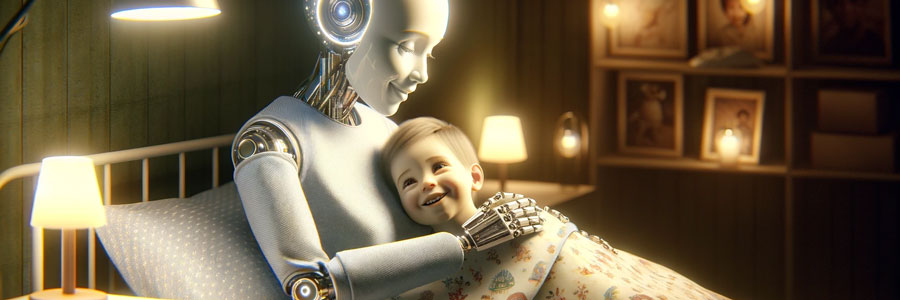

Adam and Eve lived in a world of intimate connection with God until they chose to do the one thing He had left for them to choose not to do. Such a little, arbitrary thing is a bite of fruit, especially when every other tree and bush is available to harvest. They could see that “the tree was good for food” (Genesis 3:6). Such an ordinary thing! A drop of the juice might have dribbled onto Eve’s chin. Perhaps a bit of the skin got caught in Adam’s teeth, to be easily flicked out with a fingernail. The reasoning mind can find no sense in a prohibition, and from a certain point of view, the serpent’s promise that they would not die proved true.

Too late, the reasoning mind realizes the one contingency it puts aside while considering a question. There is no sense in the rule provided that we ignore the fact it is the rule; God insisted on it. Suspend this one detail — only for the sake of argument, to be sure — and of course the prohibition makes no sense. “You certainly will not die,” said the evil one (Genesis 3:4), and he was right… provided that we ignore the death of separation from the paradise of grace.

And so humanity lived, “eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage… buying, selling, planting, building” (Luke 17:27-28). Life went on, although we lived in a place separated from God. The spiritual geography available to our immortal souls has only limited regions: Heaven, Hell, Purgatory, Paradise, and Earth. The distinction between the last two, both of which are within material Creation, is the boundary around the State of Grace. After the Fall, we lived in sinful Earth until the Christ called us to the path through a landscape of sin toward grace.

Jesus said, “for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice” (John 18:37). His interrogator, Pontius Pilate, responded, “What is truth?,” signaling that Jesus need only state unequivocally that he is not a king. Such little, arbitrary things are a few spoken words, and ambiguity is enough for the Roman governor. He can, in good conscience, go out to the Jews and say, “I find no guilt in him.” Take him back, he suggests, and I’ll keep the actual revolutionary, Barabbas.

The ploy fails, and he must side with the high priest, Caiaphas, in the conclusion that “it is better for you that one man should die” so the community can avoid worldly trouble (John 11:50). “Are you the king of the Jews?” Pilate asks, and Jesus replies, “You say so” (Luke 23:3). And Pilate does, with a sign affixed to the cross. He doesn’t believe it to be true, but what does that matter to him?

It mattered a great deal, though, to the rest of us. We have lived these 2,000 years — most of us still struggling along — with a taste of the divine connection in the Eucharist (eating and drinking) and a relationship with God inherited from the apostles through the Church. We’ve stumbled. Our leaders have erred. Yet, when we strive for the truth, we listen to Jesus’ voice calling us along the path to Paradise.

The connection has now been severed. The Church has taken a path away from truth. In “Fiducia Supplicans,” the Holy See has taken such a little, arbitrary step, and so cleverly. “The Church does not have the power to impart blessings on unions of persons of the same sex,” it admits (5). And yet, such an ordinary thing is sex. We can see that it is good for pleasure. We can see that it helps to bind people together in loving relationships. If we can find some way to affirm their attractions — not in every particular, of course, but only what seems positive in them — we can avoid the friction that modernity creates in our Church community. Isn’t it better that one antiquated hang-up should die?

If we just put aside some minor details, we can move “within the horizon” of a spiritual geography in which the Church does indeed have the power to discern the good in the “the possibility of blessings for couples in irregular situations and for couples of the same sex” (31). Redefine the meaning of the word, “couple”; give an “innovative” twist to the word, “blessing”; and ignore, as if it doesn’t exist, the distinction between blessing a person and blessing a relationship. Surely the Church will not die from such trivialities!

Except, like Adam and Eve, the Church has died out of the world of grace. In this new, all too familiar Earth, we’ll go on eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, praying and singing and baptizing. We must get as close to truth as possible. We must pull the Church as much as the path allows toward Jesus’ voice in the distance. He promised Peter, from whom the pope’s authority is supposed to derive, that upon him “I will build my church, and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it” (Matthew 16:18), so we can trust that the Church will recover the path out of sin. The pope could rescind the declaration and repent of its publication today.

Nonetheless, for the time being, we are beyond the State of Grace. While I wouldn’t impose it as a guide for others, my conscience tells me our eating and drinking can only be of the ordinary sort, and so we should not do it within the liturgy of the Mass. Pope Francis has forced us to choose between joining in the Holy See’s lie or rejecting the Holy See as a voice of truth. We are either out of communion with God or out of communion with the Church.

Human error we can tolerate in abundance, but by weaving the trap of an obvious lie, one clever, silly declaration has excommunicated us all.

I was looking for some sort of Christmas or Christian or inspirational movie to watch while I cleaned the kitchen on Christmas Eve (yes, it’s a full-movie job sometimes), and I couldn’t come up with anything. The particular problem for which I was seeking a balm is difficult to represent in cinema.

Namely, living my life, I can bring things to a point. I can have an adventure. But what then? The day-to-day grind is the hard part (even when comfortable).

As a writer and (for that matter) a business consultant, I’m well aware of story arcs. Bringing people to that moment of crisis and resolution is one thing. Helping them to trudge along day by day by day by day is another, and that’s where I, for one, have the most difficulty.

In one way or another, the response one typically finds to this problem is to set another target. When you can curl 30 pounds, now you move on to 40; do the same with your life goals. The challenging thing is that the entire series of ratcheting projects has to be part of a grand objective, and so the narrative high (or the dopamine hit) of reaching each step can be overwhelmed by the desire to reach the next one.

Movies embody this conflict. The cinematic structure requires the characters to achieve some goal, which contrasts with the lifelong requirement to sometimes rest in the moment.

The Christmas Nativity story captures this dilemma well. Some years ago (I’m tempted to say, “many”), when my eldest daughter was newly born, back before podcasts and Spotify, I went for a walk in Common Fence Point, Portsmouth, Rhode Island, on Christmas night and happened upon a dramatic radio broadcast of the Bethlehem innkeeper’s reaction upon realizing what had just happened in his barn. The performance was excellent (as proven by my still remembering it twenty years on), but the premise has always puzzled me. Did the innkeeper know? How did he know? Who else knew? (And he just left everybody out in the barn?)

The presentation of the Nativity is strange, that way. On the one hand, Jesus was born among the animals… the nondescript secret soldier, slipping under Satan’s eye by His humble beginning. On the other hand, the magi knew to travel the world to find him, and (as Handel’s Messiah puts it so memorably) “there were shepherds abiding in the fields” encountering the “Heavenly host” with an Earth-shaking song of “Glory to God!”

This, for me, is the most significant difference between Christmas and Easter, and it echoes the disconnect between the culture of the holiday and its theological import. Scrooge has a crisis to allow an engaging story, and then the rest of his life was just “keeping Christmas well.” That sort of summary of the “happy ever after” may work for movie and books, but something in the human soul recoils from the insinuation of a humdrum life.

The movie that I’ve watched every Christmas Eve for several years, It’s a Wonderful Life, comes a bit closer to my Christmas Eve mood. George Bailey has a crisis, we see a summary of each step of his life to that point, and he gets a view of what the world would have been like in the absence of his own day-to-day grind. Even so, what now? The community helps to bail him out of his problem as recompense for his good works. The viewer sheds a happy tear.

What does George do the next day? Proceed to keep Christmas well? Sure, the moral is that his ordinary life was dramatic — heroic — but is he past that, now? All the striving that kept him going, does he put it aside and simply take up an ordinary life?

Perhaps in the odd mix of anonymity and profundity in the Nativity we see the key message that Christmas is not Easter. Soon will come Lent, and then the Passion of our Lord. And the lesson there? Maybe I’m being too flip, but it seems like the New Adam, correcting Original Sin, brings us to resolution by making every inconsequential moment a Passion. Every moment is at the same time mundane and profound. Every day is Christmas. Every day is Good Friday. Every day is Easter. And every day is just another day on the road to Jerusalem.

Agnostics to whom I’m close have expressed their problem with the notion of Heaven as an inability to imagine how it could be anything other than boring. Or worse… think of the cliché of preferring to laugh with the sinners than cry with the saints. For Heaven to be heavenly, though, the experience would have to be very different — like a life in which every day is an inspiring movie.

Featured image by Jacopo Bellini on WikiArt.

The two preceding essays traced the concept of consciousness down from its highest form of abstraction, in God, to human beings. This essay turns things around and builds up to the same point from the bottom — from the stuff of the Universe.

In the beginning is the radical proposition that there is no stuff. No matter how minutely we manage to drill into matter, we will not come to a material substance out of which everything is built. The notion of particles is simply an imprecise metaphor we’ve used to help us understand the concepts.

As at the top, so at the bottom: There are only ideas. At the top, the full set of concepts equates to a personality, which is God’s, who disaggregates through relationships. At the bottom, at their most disaggregated, the concepts manifest as qualities and rules.

Articulated individually and in combination, the qualities generate points in space-time, giving each point and then combination of points identity as a thing, or a concept on a higher level. The rules create what we perceive as distance and motion by requiring, for instance, that spins, charges, and “muchness” (i.e., mass) repel or attract each other. Where some points are unable to pass through others, it is not because there exists an impenetrable wall of stuff. The metaphor, at this level, would be more like the invisible fence to keep a dog in the yard, or the force that absolutely prevents a person who is afraid of heights from nearing a high edge or a person who is terrified of public speaking from stepping out on stage, but rather than representing a phobia, the force is simply an essential rule. This identity, with its particular collection of qualities, simply cannot approach those identities, closely enough to slip by them, while their qualities draw them together.

We’ll explore how pure ideas cohere into substance when we return to the topic of reality as a relationship between observers. For the moment, the key point is that Creation consists of identities that cohere as distinct things based on the qualities that they possess. The quark is an identity. Protons, neutrons, and electrons are identities. One level up, when they combine into atoms, those are identities. And so on. They are distinct things only inasmuch as they are identified as such at a particular level of analysis or conception. Zoom far enough in on a digital picture, and you’ll see a field of dots, differentiated only by the quality of color that you perceive. Just so is the Universe-wide field of points in space-time. One must zoom out to a higher level of observation to see the patterns and discern the rules by which they take shape, and those patterns make up things — identities — on the level at which they can be observed.

It is helpful to personify identities at least to the extent of imputing to them knowledge. However, without implying consciousness, we’ll define knowledge as the recording within an identity (however fleetingly) of information through some sort of internal change. If you add a marble to a jar, the jar “knows” there has been a change; that is, it has recorded it. If the jar only has the one marble and you spin it, then the jar “knows” something is happening to make the marble move around within it.

At the most fundamental level, particles do not know that they are moving, spinning, vibrating, or whatever, because they have no means of recording that information with a change inside themselves. They are only in motion relative to other identities from a higher level of observation. Think how human beings did not know they were moving through space at great speed because that fact causes no change inside of us by which to record the information. We only figured it out through distant observations, which ultimately caused a change inside our brains to record the information.

Fundamental identities simply are as they are, and they exist underneath the rules by which they abide. From an external perspective, they may be moving toward each other, but inasmuch as nothing changes within them, the motion has no meaning for them. By definition, space-time will adjust such that opposite charges move toward each other, but that information is recorded in space-time. The charges, as identities, don’t change internally in response; they simply exist by means of the effect they have on the next-higher conceptual level.

(Note that we may find something within fundamental particles that records the changes. My argument, however, is that eventually we will reach a point at which the level of analysis cannot go any lower and the identities simply follow the rules.)

Now, just as we stepped down by level from the core idea of God to human beings, we can begin to step up from the ideas at the bottom of creation. From atoms on up to rocks, identities record information by changes imposed on them. A piece is knocked off. A crack expands. Atoms wear away from passing wind. The inanimate object only knows what is happening outside of it when there is a direct interaction that changes the object in some way.

What we categorize as life begins when an identity responds to the environment internally. At the basic level, this is still an entirely mechanical or chemical process of direct interaction, but the change occurs within the organism. The plant does not observe that sunlight exists at some elevation and grow toward it. The plan only knows that the chemical reactions that sunlight causes are not happening, and that fact produces a different internal reaction.

The most basic animals are not much more advanced. Ants, for instance, are responding to chemical changes when they follow a trail, but their processing is less direct. The detection of pheromones by antennae doesn’t mechanically change the direction in which the ant’s body moves, but the decision-making is basic.

Moving up the scale, as senses improve, they introduce a layer of awareness of the wider world, and the mechanism for processing and responding to stimuli, the nervous system, becomes able to address indirect information. The light carries information that a threat or food source is out there, and the animal responds accordingly.

The capacity for identities to respond to indirect information generates a higher conceptual level from which they can observe changes and understand new rules for how reality works. Importantly, this higher level allows animals to begin existing across time, in the future or the past, inasmuch as they can predict what might happen and respond as if it is, indeed, happening. A deer running from a wolf is not reacting to being bitten or even, necessarily, chased, but to a possible future in which that occurs. The deer exists in a range of probabilities over a certain distance of time and reacts accordingly.

Human beings achieve the next-higher level of conceptualization through our ability to think in abstractions. Spreading our existence to an abstract realm of forms, we can understand by logic another layer of rules (metarules, if you will), which we perceive not only intellectually, but also emotionally, through the chemical mechanisms of our feelings. These two species of information give the realm of forms observable influence on the world around us, by means of our responses, as well as those of other people.

In our sensing of something higher, we’ve reached the level of angels. We can’t fully know what reality looks like for them — at the level of words, as I put it while disaggregating the top-down teleology — because we lack the sensory apparatus to observe it and the cognitive apparatus to store the information. We can begin to sense the rules of the relationships that would be visible from that higher level; we can aggregate ourselves into groups, form longstanding institutions, and join in with intellectual and emotional movements that take on a life of their own; but we can’t know what it’s like to exist at the level that hovers fully above material Creation.

Obviously, each of the points made thus far in this series of essays demands more-detailed exploration, and the paths that lead away from them into specific disciplines and practical conclusions are as limitless as life itself. However, in the present sketch, the purposeful, or teleological, hierarchy of reality has now met the consequential, or nomological, hierarchy. The next step will be to decide whether they merely crash into each other or overlap from top to bottom and explore the implications our decision has for Creation and for us.

Featured image on Shutterstock.

Tracing reality from the singular Idea as it became a being and ultimately a universe — subsequently giving expression to independent ideas acting under their own wills as beings — suggests that reality is fundamentally conceptual, not material. It is fundamentally purposeful, or teleological, rather than sequential, or consequential. The metaphorical scheme to describe such a reality should therefore shift from the simple geometry used to visualize the relationship of the core concepts of Idea, Expression, and mutual Awareness to a metaphor associated with ideas themselves: language.

In this context, it is more relevant and more crucial to understand that we are merely using a metaphor to describe a concept. With quantum physics, for example, we should by now have realized that the idea of “particles” is, itself, a metaphor — one that imperfectly describes the strange ways in which these things act. This point we’ll put aside for a future essay, raising it only to emphasize the distance between language as a practical tool to describe reality accurately in our everyday lives and language as an approximate representation of a reality that is fundamentally conceptual.

Consider a book. The initial utterance that brought everything into reality — “Be” — is like the title of a book to the unfathomably brilliant person who has every word memorized and has understood it completely. The relationship of the Idea to the Expression (the Father to the Son) is a total and perfect communication whereby each knows in its entirety and simultaneity everything that “Be” signifies.

As the Being who is reality describes Himself to Himself in ever-greater detail, the separation of detail from the whole creates distinct beings. Each lower being, in focusing upon details, is no longer the Being who observes it all simultaneously, and in this way, free will arises as the choice of which detail to observe and in what sequence. The observation, the experience, and the resulting relationship with God (the unity) can differ. Each being remains an expression of God, and a participant in God’s experience of His Creation, but they cannot be God, because aspects of His Idea are unknown to them.

At one step of remove, these beings observe and understand God’s Idea at a level akin to unit headings in a textbook. They understand each unit in its entirety, all at once, but not the whole book. At this level, perhaps they are not eternally distinct; perhaps, like the explosions of flares arching from a star and falling back into it, drawn by gravity and other forces, an understanding at the level of units can collect into understanding of the entire concept of the book as the beings are drawn toward and achieve unity with the Idea. Or perhaps they remain held apart by the ontological level of observation.

Another complicated, but crucial, point emerges from the concept of beings drawn toward the unity of God. Namely, all of reality is a relationship, beginning with the mutual Awareness of the totalized Idea and its Expression. Each lesser being chooses to observe an aspect of the Multiverse (as already defined), and God expresses the Universe in response, so as to be observed in that aspect. That is, every moment is the experience of the being and its relationship with God, who is also experiencing every possible moment all at once. If a being is able to achieve perfect unity with God — meaning that it achieves the ability to experience the Universe in totality — then it becomes indistinguishable from, and therefore identifiable as, God.

Be that as it may, the layers of conceptual detail continue, and at some threshold, beings must become permanently independent because they cannot fully conceive of the whole. Within the units are beings who understand reality at the level of chapters. And then sections. And then paragraphs, followed by sentences, followed by phrases, followed by words. At the lowest level come the letters.

The metaphor stops with letters for two reasons. First, the next step would bring us into the creation of the text, its substance, and that represents a distinct aspect — the distinction between the message and the medium. Whether the message explains the medium or the reverse — that is, whether the medium exists in order to convey the message or the message appears as a consequence of the medium — is a question to which we’ll return down the road. For the moment, our emphasis is on understanding the notion of a text as a metaphor. Beings at the level of letters in the metaphor are not literally letters, so we can decide later whether and how the metaphor extends to ink and paper.

Second, taking care to stay within the frame of concepts, letters must be the base. They are the baseline of intention, of significance, of a non-incidental action to convey meaning. By whatever method the letters are made, they are the primary indicator of shapes being made deliberately with the intent to convey an idea.

Nonetheless, beings at the level of letters — human beings — can only glean meaning by stringing letters into words or maybe, if we strive and work together and build on each other’s discoveries, into phrases and sentences. In truth, we can’t even be sure which direction we’re supposed to read across the page, which makes it plausible for some to conclude that there is no such thing as coherent meaning.

With the metaphor drawn out in this way, we can think of angels and demons as beings at the level of words. Words allow no ambiguity as to whether meaning exists. A word is conceptual in its essence, unlike letters, which are arbitrarily drawn to construct a word. Yet, words can still be read across the page, rather than along the intended sentences, which is to say, they can convey a meaning contrary to God’s intent.

Evil ― which is the pursuit and construction of a meaning contrary to God’s nature ― enters reality in this way. While God is good, as is His Creation, independent wills can construct their own meaning using the substance He provides in ways that He did not intend.

At all levels of conception, the initial pattern of God replicates for all beings: idea, expression, and awareness. Each being is defined as the full set of its potential actions (meaning its potential observations of reality at its level) and its experience of choosing among them as an expression of unique will. In these terms, the greater the willfulness of reading across the page, the greater the sin.

Adam and Eve, as their Original Sin, realized that they could controvert God’s will, but that only set them adrift. In contrast, the serpent acts to convert God’s story into his own, as lunatic as it may be ― as lunatic as it must be by definition — so as to represent something separate from God and the Devil’s own. As the ancient story of the Fall also hints, it is not enough to be evil alone. To make a being’s distorted reality real, it must be shared in experience by others.

Put differently, others must aggregate their beings to the false reality because it is the observation that makes a moment real by means of the relationship between the Creator and the observer. The project of evil is to hijack the very essence of God — the beings who, as limited expressions of Him, make the Universe real in relationship with Him — to express a will that is not His.

Featured image by Vincent van Gogh on WikiArt.

Nine months ago, something in me and in reality shifted — imperceptibly, at first — and all I’ve been able to do has been to capture the growing flood of comprehension in scores of notes as each wave of thought pushes me deeper. Now I find myself feeling that I must begin to express the ideas, but with no notion of how to begin. Such ideas require years to organize and a book (at least one!) to articulate. So, perhaps I’ll strive to organize my thoughts in writing of a sort somewhere between my quickly scrawled notes and the perfected chapters I hope one day to craft.

The challenge is that, when I mention a flood of comprehension, I mean thoughts touching on, well, everything. They’re not all connected, and probably cannot be (at least by me), but thoughts and intuitions that have lingered in the air around my contemplation for decades like a damp mist have begun to take shape and to flow. Everything is making sense in a way it never has before, and I’m not sure I can convey that sense without sounding as if the exact opposite has happened to me — as if I’ve lost whatever coherence (and sanity) others might have credited to me in years past.

Where do I begin? Do I build up from subatomic particles, or down from abstract meaning? Or would it be better to trace history forward, or maybe backwards? Maybe moral principle would be a firm foundation on which to build. Or maybe intangibles like love and awe should first be painted in order to capture the imagination. Is theology primary, or physics, or history, or psychology, or literature, or… carpentry? Do I build my paragraphs around the scaffolding of thinkers and ideas with whom and with which readers may already be familiar, or do I first lay out before you that which I think is fresh and new?

I find I must abandon artifice and any plan to draw you along with me edgewise. We can only begin at the very beginning of it all and place our trust in the writings of St. Mark:

[Jesus] said, “This is how it is with the kingdom of God; it is as if a man were to scatter seed on the land and would sleep and rise night and day and the seed would sprout and grow, he knows not how. Of its own accord the land yields fruit, first the blade, then the ear, then the full grain in the ear. And when the grain is ripe, he wields the sickle at once, for the harvest has come.”

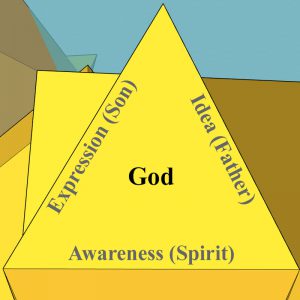

Here it is: In the beginning was the Idea. Whether He reposed thus for unknowable eons or for the merest of moments is a nonsensical distinction, because there was no time. Time had no meaning until the Idea gave Expression to Himself, like a Father begetting a Son. Begotten, not made. Between this Father and this Son, the Expression was a complete and total reflection of the Idea all at once, as if speaking a single syllable — “Be” — communicated all that being could possibly mean.

So perfect and complete was this relationship that the Idea and the Expression would have been only the Idea, itself, but for their mutual Awareness of each other, their Paraclete. This Awareness… experience… or Spirit was also complete and total with the other two, but in such a way as to make all three facets of the Trinity distinct: an idea, an expression, and the relationship between them.

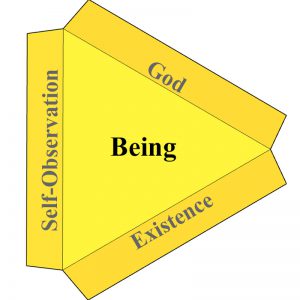

This fundamental concept, this primary identity, is God, who expresses Himself, in total, as Self-Observation, itself, and the experience of this mutual relationship is Existence. Thus emerges a second syllable (“Yahweh,” or “I Am”) and a secondary trinity: an idea, expression, and relationship forming, together, another unique identity on a more-detailed plane, and it is Being.

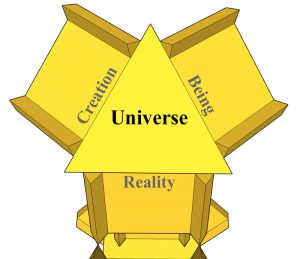

That which Being expresses is Creation, and their relationship is Reality — still total and complete, yet now with conceptual differences, such that “we all are.” This is the Universe.

Now the concept gains such abstract dimension that an image cannot capture it. (Although some artistic license produces the featured image of this post.) God expresses Himself as the Universe, and this mutual observation is Being, forming, as an identity, the Multiverse because it contains all but can be observed otherwise than as a whole. Just as the Spirit created space by which the Father and Son could be aware of each other and be different, so does this layered existence create space for God and the Universe to be aware of each other in varying depths of Being.

This framing contrasts with the understanding of the multiverse popularized in science and in fiction. In my model, the multiverse is not a higher plane on which many universes exist. Rather, the Universe contains every probability that the nature of God (the Idea) allows. What produces the appearance of multiple universes is that this one Universe can be observed from different angles.

Next, this choice of observation creates Will. One step down from the unity of God, free will creates different beings, each simultaneously following different sequences, and each defined, as an identity, according to the expression of its will. The idea of each entity is the probability of its observations, which is expressed in the action of observing one thing and not another, and the relationship between these two aspects, their mutual experience, is the entity’s consciousness of being.

Across the Multiverse every possibility exists, in a sense, just as the word “Be” contained every possible meaning of “being.” Likewise, every possible sequence of observations exists, but as a probability. Each is real, because observed by God, but it does not become what we tend to think of as “real” until it is observed by another, who by that observation establishes a unique relationship with God.