The Responsibility of Relationship

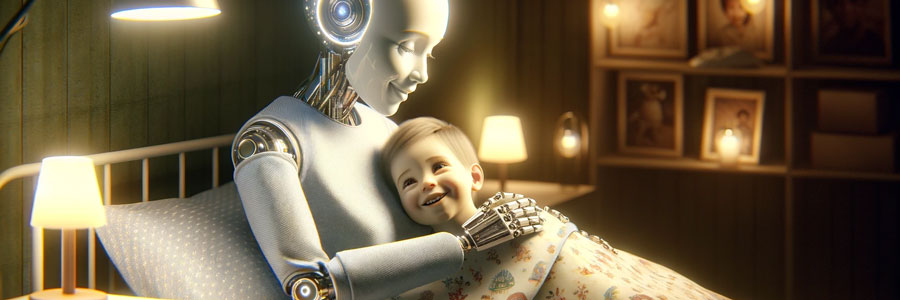

As an appropriate vignette of the near future of modern life, somebody recently directed my attention to this short movie from The New Yorker:

The title and plot description of the video cued my internal consideration of the topic of AI and relationships. Is computers’ ability to fabricate communication in ways that are increasingly difficult to differentiate from human interactions a positive development?

I can remember when the Internet was new, and on lonely nights, I’d find myself — rather than clicking through the television channels — searching for something online that felt like a human interaction. Blog comment boxes and chat rooms worked, to some degree, and social media has become nearly an addictive digital pathogen to satisfy the impulse. Turn that technological dial one click, and a person who is largely disconnected from others by the distance of screens can lose his or her sense of the importance of real people.

The distinction, here, relates to the Catholic view on end-of-life decisions. A feeding tube can be understood as akin to a long spoon, and so withholding that assistance would be immoral. A device that forcibly operates failed organs is on the other side of the line, as an “extraordinary measure,” so while we shouldn’t arbitrarily deprive people of them, ceasing their operation involves a different moral calculus than mere assistance. Such distinctions require deeper thought than many people may find natural, but it does matter whether the “person” with whom (or “which”) one communicates is a living, breathing human being.

In a dark, inverted way, “Rachels Don’t Run” points to two related reasons why. The surface reason is the unpredictability. Sure, AI could add a randomness variable, or the algorithms could become better at tricking people into sensing unpredictability, carefully crafted to evoke the response that the AI or (at first) its designers want. Nonetheless, the viewer (probably) expects an enriching outcome when Leah, the main character, breaks into the inhuman conversation and surprises Isaac.

When that outcome doesn’t materialize, the deeper reason a real human matters becomes apparent: a genuine relationship imposes responsibility. Isaac responds as he does because Leah claimed the connection without his consent. He didn’t want a genuine relationship. He wanted cooing affirmation.

Ultimately, mutual responsibility defines “relationship,” and in a world of autonomous choice, people may interpret as presumption others’ attempts to connect with them. The danger arises because this definition of “relationship” extends to God (or “life,” for those who prefer to characterize it as such). An Isaac who prefers to cultivate interactions with a digital slave lives in a solipsistic world wherein the “other” does not really exist and is there to serve him.

The viewer shouldn’t overlook the fact that Leah and Isaac both miss their mothers — representing the quintessence of responsibility — and the moment of crisis comes when Leah implies she is beginning to feel her responsibility to her mother might not mean eternal sadness about her passing. Notably, the character who reached out for a genuine human conversation was further along, in this respect, whereas the other wanted to wallow in “going through a lot, right now” — which desire seems apt to lead to long-term depression when enabled by AI.